There is never time in the future

in which we will work out our salvation.

The challenge is in the moment.

The time is always now.

-James Baldwin

Your people will change.

Your young will be more like us and ours more like you.

Your hierarchical tendencies will be modified and

if we learn to regenerate limbs and reshape our bodies,

we’ll share those abilities with you.

-from Dawn, Octavia Butler

2064: The eve of the 50th anniversary of the Ferguson Uprising. The struggle has matured and reshaped every facet of social life. But forgetfulness is endemic, so the Risers, now in their seventies, are looking to pump energy in to the movement. Among the new initiatives designed by the People’s Science Council in the aftermath of Bloody November, is a bioReparations programme that allows victims of police brutality to regenerate organs or limbs via stem cell transplantation. Over twenty thousand individuals have benefited from such procedures. Now a major new component of the programme will be unveiled for the anniversary, simply called the reGeneration. But the largest biobank in the country has been repeatedly hit by raiders intent on sabotaging the programme and selling stem cells on the white market. Aiyana Jones and her team of Keepers have to find a way to secure the cell depository and revitalize the movement.

1.

Ferguson is the Future

Fig 1. Photo published in the Ferguson Freedom Textbook (3rd

edition, 2030).

(Source: Paul Sableman/Flickr)

reGeneration (2064)

Whoever said time heals

Never had a tumor

Growing inside their belly

Mistaken for a child.

Aiyana read these words, faded on the inside flap of the reGeneration flyer. She had been sleeping with it under her pillow for the last month and the moisture must have rubbed some of the ink off. And as many times as she read it, it was no less disturbing. The thought of growing one’s own demise. What hope, or delusion, or mix of both leads one to ignore the lack of movement?

With one arm folded under her pillow, her thumb and forefinger rubbed the paper back and forth to the rhythm of ticks on her hypno-bit. Just as her fingers grew limp on the flyer and her thoughts drifted, “time is a festering, when what ails us is left to blossom”…the alarm screeched across her forehead. Not her hypno-bit, which would have been a silent buzz on her wrist. It was a bank alarm, the third one this week.

Aiyana sat up abruptly, swinging her legs out of bed and lifting herself into the chair in a single motion. Although she would reach the biobank first because most of the keepers were confined to their legs, she was also responsible for the widest perimeter. She tapped her hypno-bit twice to stop the sleep app, and reached across the bed for her coat and scarf. In the time it took to bundle up, she reached the foyer, headed out the door, and towards the bank.

…

After thwarting yet another break-in, the keepers were exhausted. They had checked the vast perimeter of the Martin Cell Depository, seeing to it that each and every cryotank was secure, and they sat in the atrium awaiting Aiyana’s return.

By now they were all accustomed to the silent screech of the biobank alarm, which only they could hear. Even so, the grinding migraines were not easy to shake. The atrium was, at turns, thumping, humming, buzzing, as the alarm resin ricocheted inside their heads.

Soon enough Aiyana returned with footage from the bank’s Eye. But as they searched for clues, it wasn’t clear how the raiders managed to cross the perimeter this time. The Keeper feed from #StemCellsMatter was no more helpful. Raiders had long found a way to distort the geotracking function so telling the difference between posts from actual keepers versus posers was nearly impossible. There was a group working on a real time authentication app to make the feed more useful, but as of now, the programmers couldn’t keep up with the code jammers.

Raiders’ desperation to stifle the 50th reGeneration was mounting. And it was getting harder and harder for Aiyana’s team to predict what new scheme they would employ. She still wasn’t sure why the weevil drones they used last week malfunctioned before reaching the main cryolab. Something beyond the elaborate security matrix seemed to be sabotaging the break-ins. As she exchanged theories with the others, running through a mental checklist of all the structural vulnerabilities that could have been compromised, the bank keeper burst in to the atrium, nearly breathless.

Aiyana reassured her that everything had been reinforced. None of the cryotanks had been touched. All of the cell lines had been accounted for, including the lines needed for the risky procedure scheduled for later that week. To mark the 50th anniversary of the Ferguson Uprising, the People’s Science Council had been working around the clock to revive one Mr. Eric Garner, the father of six who was choked to death by NYPD officers in 2014.

Holding him in cryosleep until all the necessary techniques had been honed, the Council was confident Garner could be resuscitated without incident. His last words, “I can’t breathe”, had served as a clarion call for five decades of movement building. How fitting that he would attend the 50th reGeneration in person. If, that is, the multiple stem cell transplants were successful. A lot could go wrong. Infections. Graft Failure. Cancers. If it worked, he would be the first adult to successfully undergo resuscitation and transplantation. Only children had survived after more than a month of cryosuspension.

The bioReparations programme, now in its tenth year, allowed victims of police brutality to regenerate organs and limbs using induced pluripotent stem cells. Researchers had honed the technique, taking a skin cell and coaxing it back to the stage of “pluripotency” where it could then be turned in to any other kind of cell in the human body. Because the transplanted tissue was produced using a person’s own cells, many of the complications that came from donor cells were avoided. Over twenty thousand individuals had undergone this suite of procedures… and nearly all survived.

Even so, producing a viable stem cell line takes time. And most patients could not survive on life support long enough to undergo transplantation.

***

In the early days, when the bioReparations programme was just an idea, many people actually started banking their own skin cells—a kind of insurance policy. That was before police forces had officially been disbanded and the keeper network was developed.

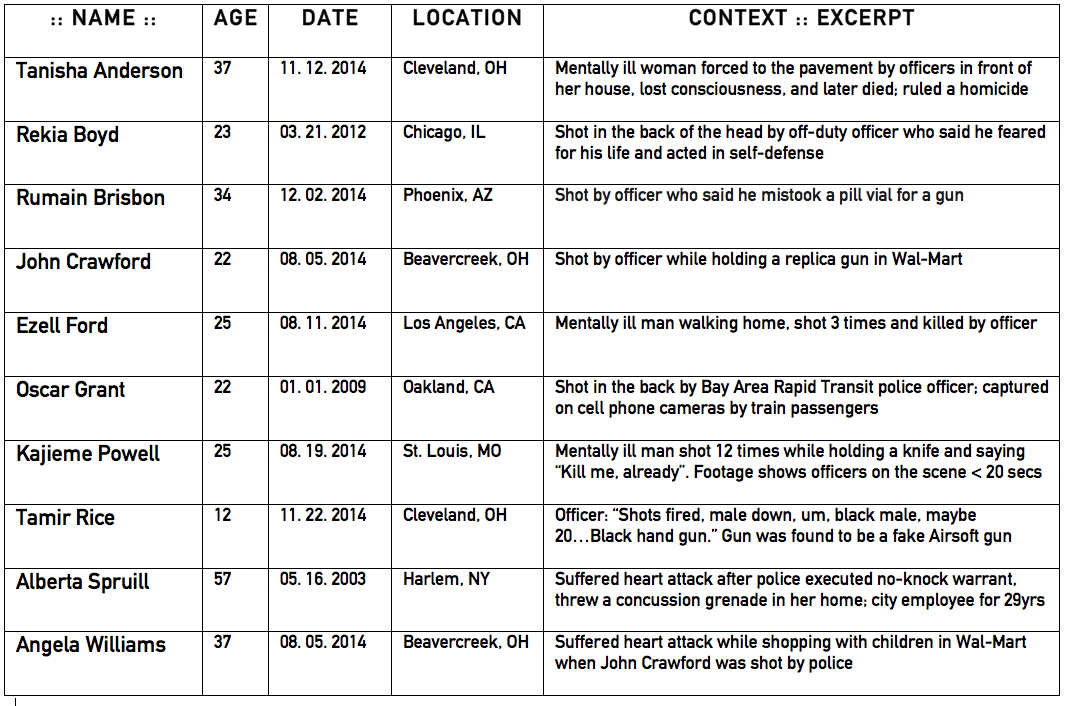

Those were the days of “every 28 hours”—children playing cops and robbers shot down on playgrounds, teenagers goofing off with toy guns in departments stores left bleeding in the aisles, mentally ill adults treated with multiple shots to the head, mowed down for walking, driving, breathing out of place. Suspects’ phones, wallets, and other objects mistaken for weapons, police reaching for firearms instead of non-lethal options, and recordings rarely leading to indictment.

Fig 2. Search Results from the Ferguson Freedom Textbook Supplemental Database. (Source: National Commission on Police Brutality, created by the Reparations Act of 2025)

Not to mention all the residual violence—bystanders dying of shock or heart failure, onlookers waking up in night terrors for years afterward, the chronic stress of living under siege, getting under the skin. Cellular memory, Social amnesia.

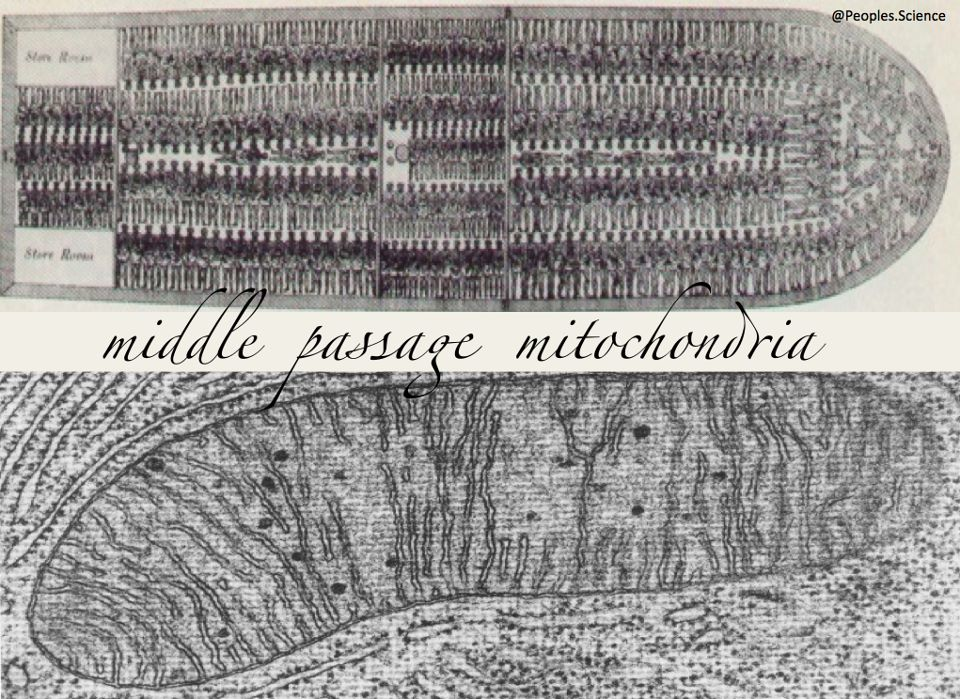

Fig 3. Image from the People’s Science bioReparations Awareness Campaign: The advertisement voice over urges, “Our ancestors fueled the New World economy, just as mitochondria power the cellular body. Harnessing our history, transforming the biopolity! Come in for a free consultation to see if Middle Passage Mitochondria is right for you.”

By the time the public health establishment accepted it as the root cause of heart disease, hypertension, and other epidemics, everyday violence was at an all time high. No way to ignore it. But the epigenetics industry that had, by then, taken the world by storm wouldn’t let go so easily. The Human Genome Super PAC successfully lobbied for an ObamaCare amendment, establishing mandatory gene-testing stations to be built alongside all health clinics. To even be seen by a healthcare worker you had to get your genome mapped. All the latest drugs were tailored to specific haplogroups. So if you didn’t know yours, forget about being treated. And if you couldn’t afford a test, you were just out of luck.

We are still trying to figure out what to do with all those abandoned testing stations.

Fig 4. Image from the Ferguson Freedom Textbook, depicting a once operative genome testing station in Baltimore, Maryland. The “textbook” is an interdisciplinary curriculum adopted by schools nationwide. (Source: www.urbanghostmedia.com)

The Keeper News exposé on “genome map forgeries” was the breaking point. The fact that people were buying knock-off maps just to get access to treatments defeated the whole point of tailored medicine. Even so, it took another decade to fully establish the People’s Science Council and begin addressing the source of so much sickness. The chronic stress of living under siege.

After uniformed officers were forced to wear body cams in 2015, the non-indictments flowed even more freely. They were, after all, responding as they had been trained. “It’s not meant to be a fair fight.” “Non-lethal responses are not in our repertoire.” To indict the officers would be to admit that the entire apparatus was defective.

The number of people who had been disabled from gunshots wounds, whether due to police aggression, gang violence, or other altercations, created a boon for the biobanking sector. Almost everyone knew at least one person who had deposited cells.

Only certified victims of police violence were covered under the Reparations Act of 2025, but anyone was eligible for a transplant if they could pay. Slowly replacing the college fund common in the early part of the century, parents and grandparents who could afford to do so, opened a tissue account for their loved ones. “Don’t cell your family short! Bank with us today”, read the floating billboards. Although most of the procedures were far too expensive for the average person, the monthly payment to keep a cell line alive was manageable.

Aiyana Mo’Nay Stanley Jones, killed by a Detroit SWAT Team in 2010, was the only person who survived cryosleep and transplants without any significant side effects.

Fig 5. Artist rendering of Aiyana Jones, currently hanging in the lobby of the People’s Science headquarters in Harlem, New York. (Source, Robert Pruitt, “Untitled 3”)

But she was a child at the time, 7 years old when an officer threw a flash grenade where she lay sleeping on her living room couch, and then shot her as a reality TV crew filmed the raid.

When the Council woke Aiyana up and implanted the new heart, lungs, and spine, at first there was only a minor graft rejection, which transplant specialists were able to control. But then came the seizures. The blackouts. And hallucinations.

With a grant from the Humanity+ Foundation, Aiyana’s transplant team designed the first of its kind Chairperson™—an apparatus that not only maintains internal homeostasis so she no longer experiences the original side effects of organ transplantation. It also includes a number of augmentations: the ability to hover up to 40mph on land or water. And an acute sensitivity to electrical fields, which enhances her ability to communicate, orientate to her surroundings, track things, and protect herself. The gold standard in second life starter kits!

Garner, on the other hand, was not only going to be the first adult, but one who required multiple regenerated organs a half-century after his first life was prematurely taken. Waking up would only be the beginning…

Postscript

This is an experiment in using fiction to know things differently. A space to think anew about the themes of my research—innovation, inequity, biotechnology, and racial justice among them. I am guided in this endeavor by three recent experiences.

The first was re-reading W. E. B. Du Bois’s short story, The Comet (1920). Set in a dystopian world where the racial status quo is momentarily overturned, it underscores the importance of storytelling in scholarly and civic praxis. The direct link he crafted between sociology and speculative fiction reminded me that we need these windows into alternative realities, even if it is just a glimpse, to challenge ever-present narratives of inevitability as it relates to both technology and society. Stories remind us that the beginning, middle, and the end could all be otherwise.

The second experience that led me to substitute story for essay was listening to writer Ursula Le Guin’s National Book Foundation acceptance speech: “I think hard times are coming when we will be wanting the voices of writers who can see alternatives to how we live now and can see through our fear- stricken society and its obsessive technologies to other ways of being, and even imagine some real grounds for hope. We will need writers who can remember freedom. Poets, visionaries — the realists of a larger reality.” Here, here, whispered the young poet I long ago wrapped in layers of scholarly silk awaiting the Academic Afterlife. Her first words upon stepping out of the Tomb of the Learned: Facts, alone, will not save us.

Finally, the third experience was completing my book People’s Science: Bodies and Rights on the Stem Cell Frontier. Towards the end of the revision process, and buried on page 172, I was finally able to articulate what I now see as the heart of the project: “But somehow imaginations go limp when we are confronted with social dis-order. For many people, the idea that we can defy politics as usual and channel human ingenuity toward more cooperative and inclusive forms of social organization is utterly far-fetched. Thus I am convinced that any institutional retooling must begin by first querying this faith in biological regeneration alongside our underdeveloped belief in social transformation. If our bodies can regenerate, why do we perceive our body politic as so utterly fixed?”1 This story is an attempt to perceive otherwise, to hold myself accountable to the query I buried in People’s Science, to formulate a critique at the power/knowledge nexus through narrative, and ultimately to fetch a different social vision that, even to the author of this tale, feels incredibly far off.

With these provocations, then, I take the idea of a sociological imagination quite literally, and envisage a not-too-distant future where race, science, and subjectivity are reconfigured differently, defiantly, and hope-fully.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to the Histories of the Future conference organizers, Erika Milam and Joanna Radin for incredibly thoughtful feedback, and the following friends and colleagues who commented on earlier drafts: Elizabeth Armstrong, Shawn Benjamin, Gurminder Bhambra, Catherine Bliss, Emily Brissette, Maryanne Boelcskevy, Zhaleh Boyd, Bridget Gurtler, Tabatha Jones Jolivet, Louis Jordan, Trina Kumodzi, Miatta Mansion, Mandu Reid, Samantha Ayana Smythe, Francoise Verges, Keith Wailoo, Melissa Weiner, and Behin White. Most of all, I extend my heartfelt condolences to the loved ones of all those mentioned in the story—by including their names my hope is to not only commemorate their lives, but to open a space for these tragedies to hasten collective struggle for a more just future.

For the final version of this story, see Ruha Benjamin, “Racial Fictions, Biological Facts: Expanding the Sociological Imagination through Speculative Methods,” Catalyst: Feminism, Theory, Technoscience 2/2 (2016): 1-28. Link

-

The theme of regeneration throughout this story is directly inspired by the work of Octavia Butler, especially in her novel Dawn where the aliens (Oankali) seek to re-populate earth with a mixed human-Oankali species (42). ↩