The Horror of Seeing Too Well: Images of X-Ray Vision

The reception of X rays during the first few years after their discovery in late 1895 provides a rich instance of the technological sublime. Wilhelm Conrad von Röntgen’s discovery of X rays on 8 November 1895 marked an apogee of the nineteenth century’s triumphalist valuation of vision. The images of previously invisible interiors, whether of living bodies or of inanimate objects were the culmination of a steadily growing belief in the medical community that vision was the supreme sense for diagnosis.1 The reaction to this discovery was extraordinary; in the year 1896 alone over fifty books and pamphlets and well over a thousand papers were published on the subject.2 X rays were welcomed as an extension of humanity’s ongoing progress, its conquest of yet another frontier. And this progressive flavor quickly became imparted to all manner of unlikely products—X-ray headache tablets, X-ray stove polish, even X-ray juice presses.

Fig. 1a An advertisement for an \“X ray\” analgesic [source].

Fig. 1b X-ray stove polish. Author\’s collection; see also here and here.

Fig. 1c X-ray brand juicer, Ebay

As cinema historian Yuri Tsivian has argued, X rays, along with the microscope and cinema, participated in a rhetoric of “penetrating vision,” offering images that ran the risk of showing too much.3 Indeed, the fantasies surrounding X rays clustered around fears about privacy, from such peculiar artifacts as laws forbidding the use of X-ray opera glasses and manufacturers hawking lead-lined underwear, to beliefs that X rays would allow viewers to see other kinds of invisible domains, such as thought, which was at the root of beliefs in X-ray telepathy. Anxieties mounted about how the vision of the future would permit rampant indiscretion. More generally, X rays demonstrate how visions of the future are often tied to notions of future vision, i.e., transformations in perception brought about by technological change. Seeing into the future frequently involved a change in how we might see.

Fig. 2a “Le costume de demain.” Detail from A. Robida, “Variations sur les rayons X,” La Nature 24 (9 May 1896): 91.

Fig. 2b Advertisement for X ray novelty glasses

An early trick film, The X Rays (1897), uses the new technology to satirize romantic conventions.4 Here a photographer with a device labeled “X Rays” transforms a scene of comic romance by showing the courting couple as a pair of skeletons. The withering gaze of the X rays reveals the vanity of the flesh as a farce. A darker shade of this trope finds an articulation in George Griffith’s “A Photograph of the Invisible,” in which a certain young Denton has been thrown over by his beloved, Edith.5 His friend, Professor Grantham, a chemist and physical investigator by profession, but with an interest in photography as well, promises him “revenge that shall be purely scientific, beyond the reach of all human law, and I think I may say, absolutely unique.”6 The men concoct a scheme to punish Edith that revolves around producing an X-ray image of her. When she receives the image, it has a spectralizing effect on her: “Neither of them said anything when they first saw what was underneath, but the blood rushed to his face till it was almost purple, and died out of hers till it was grey and white and ghastly—the face of a corpse, but for the two bright, glaring eyes that stared out of it.” Edith’s husband is struck down by a nervous malady, and she ends up in a private insane asylum, morbidly photophobic.

Like any visual prosthesis, X rays threw the limits of human vision into stark relief. As Linda Henderson has emphasized in her work on the reception of X rays by the avant garde, “these invisible rays . . . clearly established the inadequacy of human sense perception and raised fundamental questions about the nature of matter itself.”7 A particularly prominent aspect of X rays was their “thanatographic” qualities, making the ends of the human visible in an image of death.8 Even more than had photographs, X rays troubled the boundary between living bodies and inanimate objects.

C. H. T. Crosthwaite’s “Roentgen’s Curse,” (1896) offers another vivid document of the ambivalent reception of Röntgen’s discovery. Near the beginning of the story, the narrator and protagonist, a former bacteriologist and analytical chemist, now retired thanks to an inheritance, and recently back from India where he had been involved in the “chase after the cholera microbe” introduces his tale: “I was on the track of a great discovery. I was sure of it. A little more time, a little more toil, and the reward would be mine. I, Herbert Newton, should be hailed as the greatest benefactor of the human race in modern times.” (469) Newton succeeds in inventing a fluid that when applied to the eyes gives the user the ability to see with X-ray vision.

Newton tests the fluid on his dog, and the dog goes insane. This rather arch moment of foreshadowing is lost on Newton, however, who proceeds to administer the liquid to his own eyes. When his wife and son visit him, he regrets his decision. “I dared for one moment to look again, and in that one moment I suffered enough to make me regret for ever the ambition to see with the Divine eye. Two living skeletons walked in, the larger leading the little one by the hand; two chattering, gibbering skeletons. . . Oh God! How terrible! There at my knee was a little skeleton, mouthing at me and aping the motions of life. I closed my eyes again, and my tongue refused to speak.”9 Newton is brought to the edge of madness and total collapse before the effects of the fluid wear off and he returns to the bliss of normal, limited vision.10

Edmond Hamilton’s “The Man with X-Ray Eyes” (1933) similarly emphasizes the personal costs of increased knowledge.11 The story’s protagonist, David Winn, is a journalist who implores Dr. Jackson Homer to test his new advance on him, which will render inorganic matter invisible. He believes this type of vision will allow him to “get stories no other reporter can get,” in part thanks to his newly acquired skill of lip-reading. The scene in which Winn sees differently for the first time underlines the metaphorical payload that the enhanced view carries, however: “It came to Winn as he emerged into the street that his new eyesight gave him more than the power to look through walls—it gave with it the power to look through the falsities of ordinary existence into the true hearts of men.”12 His insights into the meetings of politicians and industrialists, the inner workings of a prison, a hospital, and an “insanity-hospital” evoke “revulsion” and disgust. The “grotesque spectacle of the city” overwhelms him, and the images of unhappiness begin to threaten his wellbeing:

In his soul, a horror was expanding that he could not conquer…. He was sick, sick unto his soul. Why, he cried to himself, had he ever been so mad as to let his eyes be changed? Why had he not realized what it would mean? All the wretchedness and wrong-doing and horror of life that was hidden from other men by walls would always be staring him in the face. He would see them always with eyes that penetrated all concealment.13

Society’s pervasive rottenness strikes him most powerfully when he realizes that even his fiancé is concealing her true feelings about him.

The story concludes with Dr. Homer at the morgue, where he identifies David’s body. David’s pose in death is telling: “He lay with body tensed, and with one hand flung palm-outward against his face, across his eyes.”14 Dr. Homer’s interpretation of this gesture encapsulates the recurring anxiety surrounding these tales of enhanced vision: “He was trying to keep from seeing everything. For he saw everything just as he wanted to, and it was too much for him. God keep us blind to this world! Prevent us from the horror of doing what he did, of seeing too well.”15

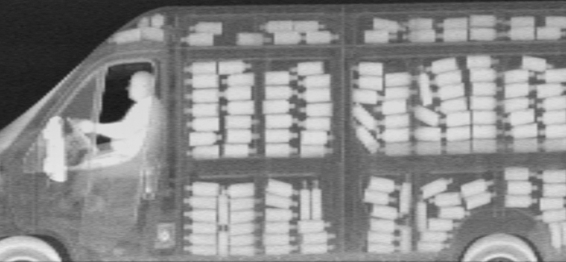

This turn away from enhanced vision accorded on the one hand with a conservative form of technophobia, a call to ignore certain kinds of knowledge in favor of the status quo. But this doubt about the benefits of progress also constituted a critique of triumphalist valuations of technically enhanced vision. As yesterday’s X-ray fantasies became increasingly realized in various surveillant techniques, yesterday’s skeptical responses can seem surprisingly prescient.

Fig. 3a. X ray vision today; a ZVB (Z Backscatter Van) from AS&E (American Science and Engineering), “the top-selling mobile X-ray inspection system in the world.”

Fig. 3b. An image generated by the ZVB system. [source]

As a media historian, I am particularly interested in how mass culture registers ambivalence surrounding new technologies of vision. My use of the “sublime” designates conceptions of overwhelming media experiences, where technologies extend the human sensorium into new environments that reveal exciting and sometimes terrifying vistas.16 This essay’s consideration of a selection of stories that register an anxious reception of the X ray will be extended in subsequent contributions, where I will take up the microscope, the telescope, and the ophthalmoscope, drawing on examples from both cinema and literature.

-

See Stanley Joel Reiser, Medicine and the Reign of Technology (London: Cambridge University Press, 1978). ↩

-

For a selection of responses to the discovery of X rays, see Otto Glasser, Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen and the Early History of the Röntgen Rays (London: Bale and Danielsson, 1933). ↩

-

Yuri Tsivian, “Media Fantasies and Penetrating Vision: Some Links Between X-Rays, the Microscope, and Film,” in Laboratory of Dreams: The Russian Avant-Garde and Cultural Experiment, ed. John E. Bowlt and Olga Matich (Stanford, CA.: Stanford University Press, 1996), 81-99. Tsivian notes that the thematization of the X ray’s penetrating gaze in early cinema often belonged to a de Lorde Grand Guignol tradition that emphasized the terrors of technology. See also Tom Gunning, “Heard over the Phone: The Lonely Villa and the de Lorde Tradition of the Terrors of Technology,” Screen 32/2 (1991): 184-96. ↩

-

G. A. Smith, The X Rays (1897), British Film Institute National Archive. ↩

-

George Griffith, “A Photograph of the Invisible,” Pearson’s Magazine 1 (January-June, 1896), 376-80. ↩

-

Griffith, “A Photograph,” 376. Grantham further describes himself as, “Not a photographer in the ordinary sense of the word, but rather an excursionist in the outer and least known realms of science” (378), listing “chromatic photography,” spirit photography, and a form of Galtonesque composite photography as belonging to his interests. ↩

-

Linda Dalrymple Henderson, “X Rays and the Quest for Invisible Reality in the Art of Kupka, Duchamp, and the Cubists,” Art Journal 47/4 (1988): 324. ↩

-

For “thanatographic,” see Akira Mizuta Lippit, Atomic Light (Shadow Optics) (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2005). ↩

-

Crosthwaite, “Röntgen’s Curse,” 475-7. While a prominent mode of reception surrounding early cinema figured it as a way of conquering death because of its ability to preserve an image of motion, particularly the image of loved ones in motion, there was another current of reaction to the first exhibitions, one of unease, and the uncanny reactions to X rays are related to this other of the vivifying gaze. For the best examples of the uncanny reaction to early cinema, see Maxim Gorky, “The Kingdom of Shadows,” and O. Winter, “The Cinematographe.” ↩

-

In a subsequent post, I will elaborate on how X—The Man with the X‑ray Eyes (Roger Corman, 1963) recapitulates many of the motifs from Crosthwaite’s story. ↩

-

Edmond Hamilton, “The Man with X-Ray Eyes,” Startling Stories, 14/1 (1946), 63-4; originally published as “The Man Who Saw Everything,” in Hugo Gernsback’s Wonder Stories 5/4 (1933). ↩

-

Hamilton, “The Man with X-Ray Eyes,” 67. ↩

-

Ibid., 68. ↩

-

Ibid., 69. ↩

-

Ibid., 69. An anecdote about a supposedly “lost” final shot of X-The Man with the X Ray Eyes, where Xavier, after his self-enucleation, cries, “I can still see!” offers a similar image of overwhelming, inextinguishable, vision. ↩

-

Also useful for me here is Carolyn Marvin’s concept of a “media fantasy,” a cultural projection of possibilities cast upon emergent media; see Carolyn Marvin, When Old Technologies Were New: Thinking about Electric Communication in the Late Nineteenth Century (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988). ↩