Words fail us when it comes to talking about nuclear war. We can coin new terms (“megadeaths”), but in other aspects it seems that language itself breaks down. How can we discuss the impossibly long half-life of plutonium (24,000 years) or the climatic wintering caused by hurling millions of tons of particulate matter into the atmosphere — unpleasant matters, to be sure, but also ones that seem to transcend the human scales to which our languages are adapted? Another thing: nuclear war hasn’t happened (except for two bombs detonated over the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945, which in today’s parlance would count as a “limited nuclear conflict”). Talk about global thermonuclear war is speculative. All discussions about it are, to some degree, fictional, worlds created out of language. In this essay (and the series that follows it), I am going to take a tour the future of language in the aftermath of nuclear war, guided by both the imaginative novels of the past and the contemporary theories of linguists that were deployed (explicitly or implicitly) in them.

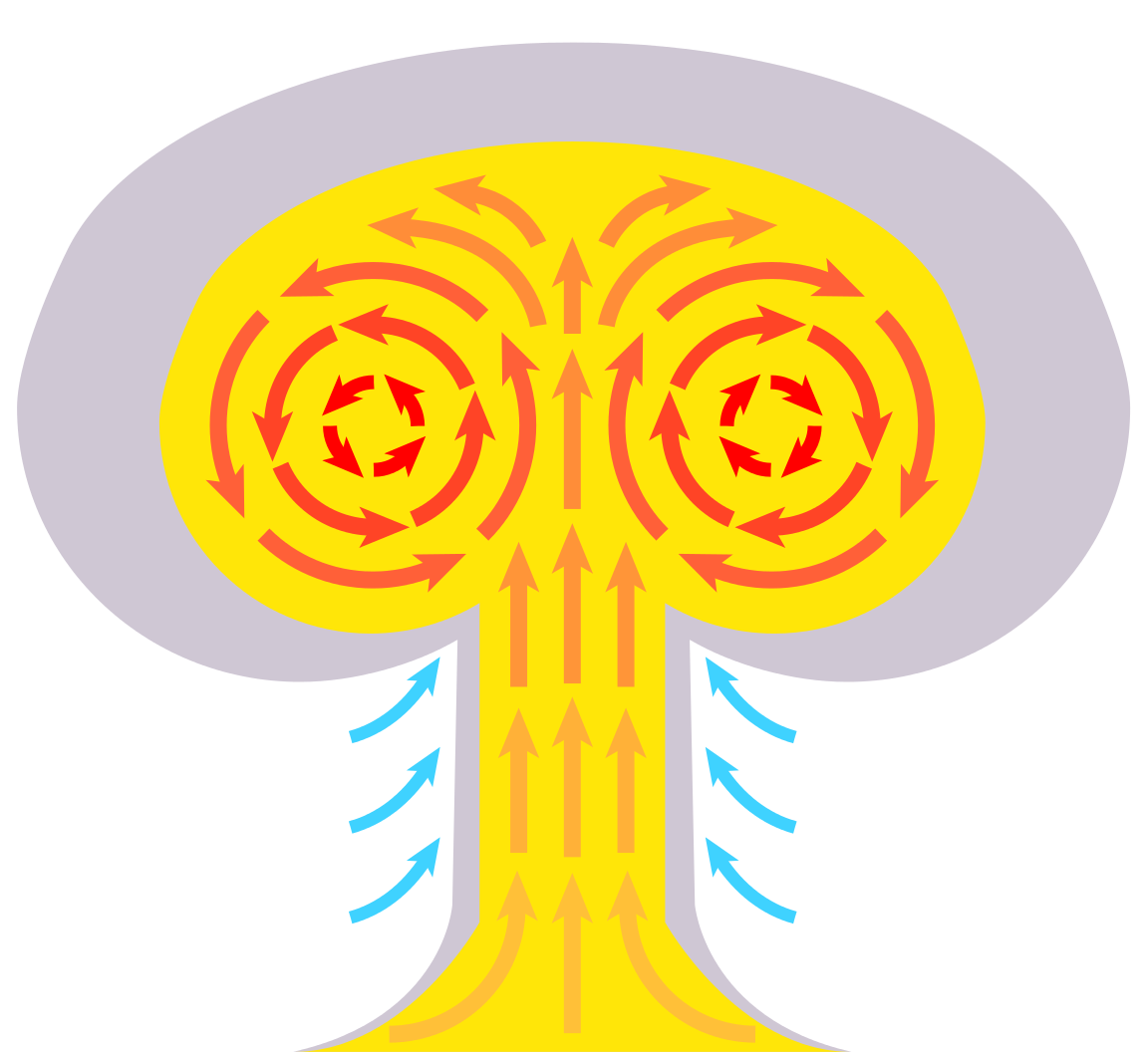

A visual schema of the convection currents of a nuclear mushroom cloud, a much easier and more predictable rendering than figuring how to talk about what happens outside and after the cloud.

Before delving into that, I need to clarify what we mean by the “beginning of the Nuclear Age,” since how one defines beginnings often heavily structures the kinds of endings one gets (and what is nuclear war if not an ending and, possibly, a beginning?). Everyone seems to agree that the Nuclear Age began at a definite moment, but without a lot of consensus about when that was. Was it in December 1938, when Otto Hahn and Fritz Strassmann announced to the world the splitting of the uranium nucleus? On 2 December 1942, when Enrico Fermi supervised the first nuclear chain reaction under Stagg Field at the University of Chicago? Other possible dates include 16 July 1945, with the first nuclear explosion of the Trinity test in Alamogordo, New Mexico, and 6 August 1945, with the destruction of Hiroshima.

All of these posited origin moments hover around the physical reality of nuclear fission and hence nuclear bombs, but we could take a softer beginning, rolling as far back as the 1914 publication of the book that coined the term “atomic bomb”: The World Set Free by H.G. Wells (who will return in a later installment of this series). Whenever the Nuclear Age began — and for now, let’s loosely place it around World War II — it immediately sparked the imagination, especially on the part of Americans, about what nuclear war and its aftermath would be like.

There are a lot of ways to refer to nuclear war, and in what follows I’m being absolutely literal. Not metaphors about loss and apocalypse (although they might also be that), but actual descriptions of nuclear holocaust and its aftermath — well, as literal and actual as talking about nuclear war can be. Since any such discussion about the consequences of thousands of bombs going off is necessarily speculative (given the evident absence to date of a global nuclear war), people must contemplate it in analogy to things that have already happened, events they believe they understand well enough to project into the unknowable. In my own analysis —which focuses on novels— I mostly ignore nuclear film, nuclear theater, nuclear sculpture, nuclear painting, and many other imaginations of the post-apocalyptic. Novels are made of language and language alone, and it is impossible to talk about them without constantly confronting the dilemmas of nuclear language. That is my quarry here. Explicit depictions of nuclear war, explicit discussions of language.

There’s a pattern to the analogies and frames that authors have used, and that pattern is historical, by which I mean that distinct modes have assumed currency at different points in time, rising to prominence at particular moments and then slipping into the background (although never fading away). Scrolling forward from World War II, I see three prominent patterns.

The earliest group of novels thought of nuclear weapons as similar to other weapons. Firebombs on steroids, if you will. (Wells offers an archetypal example, embedding atomic warfare in the context of aerial bombardment, which he forecast in The World Set Free.) Such depictions of nuclear war called to mind the obliteration of Dresden spanning Valentine’s Day, 1945, or the devastation of Tokyo during “Operation Meetinghouse” on 9-10 March of that same year. In this kind of articulation, novelists were simply following the nuclear specialists, the “wizards of Armageddon.” The first of these nuclear mavens, Bernard Brodie, immediately converted his PhD musings about naval strategy (Yale, 1940) to become the earliest visionary of what came to be called mutually assured destruction. In November 1945. Years before there was anyone mutual to assure destruction. (That would happen, or begin to happen, in late August 1949, when the Soviet Union detonated its first test device).

With the advent of thermonuclear (hydrogen) bombs, even the most diehard of the extrapolators from the conventional thought that the nuclear called for a new mode of analysis. (Brodie soon foresaw what he dubbed “the absolute weapon.”) There was just no analogy in the extant arsenal, but there might be an analogy in . . . gambling, union-management struggles, or coaxing your children into babysitting. Game theory was born in 1944 at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton under the pens of John Von Neumann and Oskar Morgenstern, and was transmuted by the late 1950s into a widely applicable — and enduring — tool for mathematicians, strategists, and economists. (Take, for example, Thomas Schelling, who won the 2005 Nobel Prize in Economics for applications of game-theoretic reasoning to just about every feature of social interaction, including nuclear negotiations, especially in his path-breaking 1960 book, The Strategy of Conflict. The nuclear imaginary is muted here, but it is never absent.) Herman Kahn, of the RAND corporation in Santa Monica, California, can stand as a representative for this second line, albeit an idiosyncratic exemplar more devoted to systems analysis than game theory proper. Such thinkers served as models of characters or even plotlines for a certain subset of novels, and in those, we can read nuclear war through matrix-rimmed glasses.

Strongly speculative nuclear literature formed a third path alongside these first two clusters of nuclear imaginaries, and it forms the primary source base for these essays. This genre is predominantly, but not exclusively, Anglophone, with a heavy concentration in the United States. (I have my suspicions about why this is so, which will manifest in due course.) Since we will predominantly be traveling during the high days of Cold War rationality, a time where classification in both major senses was all but obligatory, let’s break down this third, and last, category, into four general domains:

a) Flashpoint: These novels are essentially thrillers, chronicling the break-out and unfolding of nuclear war, or the near-miss of a complete apocalypse, or the reduction of what could have been the End Of The World into “merely” a limited nuclear destruction. Exemplary here are Robert Colborn’s The Future Like a Bride (1957), Peter Bryant’s Red Alert (1958), Eugene Burdick and Harvey Wheeler’s Fail-Safe (1962), and William Prochnau’s Trinity’s Child (1983).

b) Shelter: Such novels focus on short-term survival in the wake of thermonuclear destruction. To set a somewhat arbitrary limit, these novels focus on the first five years, and explore how people attempt to hold together the structures of civilization as those teeter and (often) fall — the greatest threat being vigilantes rather than radiation-induced birth-defects. Here I would point to Philip Wylie’s Tomorrow! (1954) and Triumph (1963), Nevil Shute’s On the Beach (1957), Pat Frank’s Alas, Babylon (1959), Mordecai Roshwald’s Level 7 (1959), Whitley Strieber and James W. Kunetka’s Warday (1985), and Cormac McCarthy’s The Road (2006).

c) Sepia: Nuclear war is long past, but not forgotten. A few generations (say, 25 to 75 years) have gone by, but there are those alive who remember what the world was like before the cataclysm, or at least who have heard about it firsthand from survivors. The antediluvian world has shifted into a haze of nostalgia or condemnation, and individuals attempt to piece together a new world rather than save the old. This is a very large genre, including Leigh Brackett’s The Long Tomorrow (1955), Kim Stanley Robinson’s The Wild Shore (1984), and David Brin’s The Postman (1985), Denis Johnson’s Fiskadoro (1985).

d) Epic: These novels explore the longue durée, typically a few hundred to a few thousand years after thermonuclear war, when essentially all that remains of our contemporary civilization are ruins that the novel’s characters have to struggle around. These texts veer closest into the classic science fiction of space opera or fantasy epic, since readers need to be introduced to a whole new world: William M. Miller, Jr.’s A Canticle for Liebowitz (1959), Robert Heinlein’s Farnham’s Freehold (1964), Russell Hoban’s Riddley Walker (1980), Paul O. Williams’s The Breaking of Northwall (1980), and Poul Anderson’s Orion Shall Rise (1983).

There is a lot of bleed between these categories. Farnham’s Freehold, for example, is both a Shelter and an Epic, while Brendan DuBois sets his Resurrection Day (1999) in the temporal aftermath of Shelter novels but the book is structurally a Flashpoint narrative. And although William Golding’s classic The Lord of the Flies (1954) takes place in the immediate aftermath of a nuclear war, his protagonists being children shifts the story closer into Sepia in terms of genre. Nonetheless the general pattern is useful. In the essays that follow, I will concentrate for the most part on Sepia and Epic novels, because their temporal setting and duration lend themselves to discussion of language.

Although not always front and center. When reading through these novels, many times language is only an afterthought, or an incidental plot device. Language is simply not what most authors are thematically preoccupied with. Instead, they pose two general questions:

Is mankind irreducibly evil? In the vein of original sin, are we condemned to an inexorable path toward technological destruction powered by intellectual hubris?

How do we preserve old knowledge and create new knowledge without the structures of contemporary civilization?

These are fascinating themes, no question, and the novels in question discuss these directly and indirectly in profound ways. In creating worlds that allow explorations of such complex questions, authors sometimes reference the linguistic background against which - and sometimes, through which — the plot unfolds. My interest in these essays is not the aspects of the books that make them “nuclear.” I simply want to exploit the fact that languages can only remain semi-standardized across broad distances with the constant support of an elaborate infrastructure (an educational system, commerce between urban centers, media, etc.). To imagine a world where those infrastructures break down, we need something massive, and massively destructive. Nuclear war fits the bill. This is my central concern; it is not usually that of the authors. In these novels, if language comes up explicitly, it is often casually, as an afterthought. In this, it isalmost like the earlobes and cufflinks in a classic oil painting, to use the analogy described in a classic essay by Carlo Ginzburg: a telltale sign where the author’s views are expressed nakedly, precisely because they are less deliberate. This allows me to explore how the theories developed within the science of linguistics of the day helps us understand the changing contexts of production of these novels, and in turn how these novels help us understand the historical evolution of postwar linguistics.

Language is intimately linked to time, especially in Sepia and Epic texts. Outside this admittedly esoteric nuclear genre, there are very few novels that traverse the longue durée, and surely part of the reason is the difficulty of maintaining continuity (of characters, of plot) over such scale. Here, language helps. Readers have a folk understanding of what “a language” is, which works as a built-in clock to track change over time. Since, historically, long duration is often marked by linguistic unintelligibility, fiction writers can use it to mark the passage of time. If English becomes something not mutually intelligible to various one-time members of the Anglophone language community, then readers are meant to understand that a long time must have passed. By following sociolinguistic processes like language change, language drift, and pidginization in speculative fiction of the nuclear age, we can trace a history of the future as a series of gradual changes, accreting like dead coral on the body of a reef.