Visions of our evolutionary futures depend fundamentally on our perceptions of the past. More specifically, they are built from a trajectory that connects the past to the present and extends into the unknown years that lay before us. Ask a biologist to predict the future of human evolution and she will likely tell you to stick to science. If you persisted, you might learn that creating any plausible picture of the future requires at least two additional factors: a firm grasp of the biological principles currently affecting our survival and reproduction, and a sense of when to begin the extrapolation.

Easier said than done. In the late 1960s, for example, the chasm between our evolutionary past and our technological future yawned wide. If the hypothesized Dawn of Man ostensibly represented a fundamental transition to a fully human way of life, the dramatic achievements of the Space Age seemed to poise humanity once again at the brink of irreversible transformation.

During that decade, paleoanthropologists like Mary and Louis Leakey grabbed headlines as they uncovered fossil hominins in the northern plains of recently decolonized Tanzania.1 The layers of bones they meticulously documented gave physical form to our remote ape-like ancestors. Olduvai Gorge, where they toiled, remains an important paleoanthropological site today. Over the years, specimens found there and throughout the rift valley in eastern Africa have shaped our vision of deep human history as a great branching tree of now extinct species. Bipedalism, a capacity for language, the ability to manufacture complex technologies and conceptualize “tomorrow”—these traits evolved over millions of years. Many scientists in the ’60s, however, still believed it likely that humans became human in a far more temporally coiled moment, as each trait spawned others, in a maelstrom of positive feedback.

Although Americans reacted with dismay at the Soviets’ success in launching the first artificial satellite (1957) and then again at Yuri Gagarin’s orbit of Earth (1961), they cheered at the end of the decade as Apollo 11’s landing capsule settled onto the surface of the moon on 20 July 1969 and listened intently as Neil Armstrong intoned through gentle static… “That’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.” The emotional investment in the Space Race emerged as a function, too, of the growing stockpiles of nuclear weapons and fears that the Cold War might turn hot.2 Humanists and scientists alike reasoned that the world they now inhabited operated according to a new — and therefore confusing — logic.

Psychologist Charles E. Osgood called attention to this imbalance between our technological facility and our incapacity for rational self-control in face of nuclear proliferation in his 1962 treatise, An Alternative to War and Surrender. We must let go of our “Neanderthal mentality,” he wrote, and adopt more cooperative strategies of behaving. Only through small gestures of trust could policy makers break the cycle of escalating mistrust. He called his theory GRIT, for graduated and reciprocated initiatives in tension reduction. He reasoned that by consciously adopting psychological strategies that fostered trust, individuals and governments alike would be able to escape the raw emotional contests that reduced complex issues to simplistic dualisms. It was long past time, Osgood contended, to transition from a psychology conditioned by our dark evolutionary past into a more hopeful, rational, future.3

The view that human nature was intrinsically out-of-date extended to students of animal behavior as well. Take, for example, ethologist and popular author Konrad Lorenz and his enduringly popular On Aggression.4 In it he suggested that humans lacked an evolved capacity for reckoning with our newfound capacity to kill at a distance with the aid of missiles and bombs. True predators (with dangerous physical adaptations like the claws and sharp teeth of carnivores) rarely killed each other in male-male contests. When two dogs fight, for example, the loser can signal his defeat, abandon the fight, and run away—potentially injured but alive. Doves, on the other hand, don’t possess ritual submission gestures in their behavioral repertoire, so an aggressive dove might peck an unwanted cage-mate to death. For Lorenz, humans were more like doves than dogs, and that made us incredibly dangerous. Worse, with new technologies like atomic bombs, antagonists never faced each other and so would not be able to signal cues of submission even if humans had them. Yet again, our technological future worked at odds with our evolutionary past.

In each of these cases, the biological essence of what it meant to be human was immutably fixed in the evolutionary past, brought to a grinding halt by the development of culture. This paradox of the nuclear age—nature as past, nurture as future—has proved quite resilient.

More recently, public fascination with immutable human nature has lead some nutritionists to suggest that we should eat “paleo,” eliminating from our diet all foods derived from our supposedly post-evolutionary past: processed foods as well as cultivated and domesticated grains and vegetables. Yet, as zoologist Marlene Zuk convincingly argues in Paleofantasy, early humans were not perfectly adapted to their own environmental conditions: they were adapted enough not to go extinct, which is all that was required.5 Their physiologies, just like ours, were a series of tradeoffs; their diets, like ours, varied widely with geography and climate. Nor has human biological evolution stopped. Humans continue to evolve both biologically and culturally. And the future of humanity is always in the process of becoming (to paraphrase Osgood’s hopeful sentiment from the opening of An Alternative to War and Surrender).

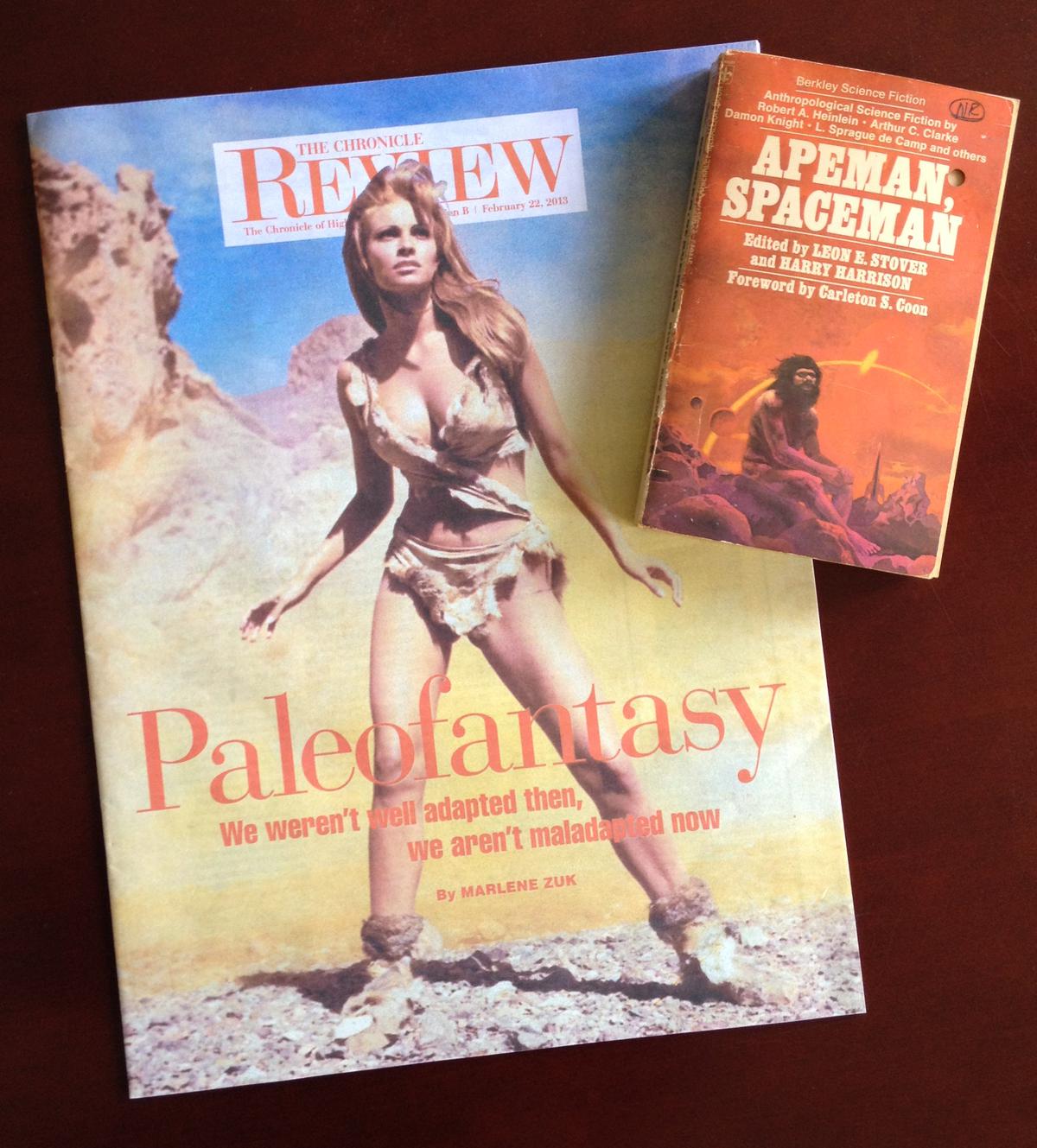

When The Chronicle Review published an excerpt of Marlene Zuk’s Paleofantasy (February 22, 2013), they chose as their cover image a still of buxom Raquel Welch starring in the campy One Million Years B.C., released in 1966. Clad in her fur bikini, she provides a sunny contrast to the contemplative, hirsute, and naked “Apeman” on the cover of Leon Stover and Harry Harrison’s edited collection of anthropological science fiction—Apeman, Spaceman (New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1968).

When George Orwell penned his anti-totalitarian dystopia—Nineteen Eighty-Four: A Novel—he placed the following motto in the hands of the only political Party, “Who controls the past […] controls the future: who controls the present controls the past.”6 Orwell’s bleakness not withstanding, he was right. In science, of course, there are many parties claiming the present and, as a result, many futures. For a historian, the multiplicity of futures is a boon. Reading past iterations of projected futures allows us to uncover (following Orwell) the underlying assumptions about the present that scientists mobilized in constructing their theories. Additionally, we can track whose version of the future proved persuasive and how scientific consensus changes. The future is a great historical resource.

How much, then, did the tendency to see human nature as significantly out of time with our current technological capacity reflect the social and scientific convictions of the Cold War? And, if it was located firmly in that historical moment, how do we make sense of the paleo diet? Many biologists agreed that when humans became human — however you might define that — a new form of evolutionary process came into being. Our very human capacity for culture, language, and learning, signaled a rupture with our physical, zoological past. This new kind of evolution has gone by a variety of names. Paleontologist George Gaylord Simpson in 1949 contrasted the older “organic evolution” with “cultural evolution” and surmised that whereas the former proceeded by “interbreeding,” the latter instead progressed as a result of “inter-thinking.”7 Population geneticist Theodosius Dobzhansky similarly suggested seven years later that understanding the legacy of humanity required accounting for culture. “The evolution of man,” he wrote, “represents one of the rare instances of the emergence, in the history of life, of a radically new kind of biological organization, and of the adoption of an entirely new way of life.”8 Both agreed, as a result, that the only destiny or purpose guiding humanity’s future was our own free will.

Writing after the Second World War, Simpson and Dobzhansky struggled to make sense of the trauma that had torn Europe apart in the previous decades. They took their professional standing as scientists seriously and felt a commensurate ethical responsibility to correct popular misunderstandings about the theory of evolution. In doing so, they hoped to build a more equitable world for all human cultures and ethnicities. Articulating a truly universal human nature, anchored in our shared evolutionary past, and distinguishing humanity from “mere animals,” thus became an intellectual project weighted with political and moral valences. We can read in their publications a flat denial of eugenic racial typologies as pseudoscientific and socially harmful, as well as an abiding hope that as a result of “inter-thinking” and the production of new knowledge, the future of humanity was bright with promise.

In editing an anthology of anthropological science fiction, anthropologist Leon Stover also highlighted this dual identity, which he read as the twinned concerns that preoccupied physical and cultural anthropologists: Apeman, Spaceman (published in 1968).9 Language and symbolic thought made culture possible, Stover argued, and culture in turn transformed human biology. Ever since, culture and the complex technologies we produce with it have acted as extensions of the human organism, accumulating faster and changing more dramatically than genetics. These rapid alterations in our relationship with our built environment necessitated new means of communication and pedagogy—hence Stover’s fascination with science fiction as the perfect medium to reach a new generation of tech-savvy undergraduates.

When Osgood quipped, “Perhaps Modern Man, with his head stuck in the sky, still has Neanderthal feet that are stuck in the mire,” his contrast of a chromed present and a fur-trimmed past fit well with the regnant evolutionary theory of the day.10 But he feared the fate awaiting humanity was likely to be a post-apocalyptic scramble back to civilization rather than an international collaborative jaunt through the stars. The iconography of a primitive past maintained its Cold War grip on public and scientific imaginations because it also made manifest a monstrous potential future.

-

Louis Leakey had a particularly friendly relationship with National Geographic. See, for example, Louis S. B. Leakey and Robert F. Sisson, “Exploring 1,750,000 Years Into Man’s Past,” 120/4 (October 1961), 564-589; Melvin M. Payne, “The Leakeys of Africa: Family in Search of Prehistoric Man,” 127/2 (February 1965), 194-231. ↩

-

Ironically, one of the scientific tools that emerged from research into radioactivity included the dating of hominin fossils with a Potassium-Argon “atomic clock”—see Garniss H. Curtis, “A Clock for the Ages: Potassium-Argon,” National Geographic 120/4 (October 1961), 590-592, published in the same issue as Leakey’s announcement of 1,750,000 year-old Zinjanthropus (now, Paranthropus boisei). ↩

-

Charles Osgood, An Alternative to War and Surrender (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1962). For a fuller exploration of GRIT, see Paul Erickson, Judy L. Klein, Lorraine Daston, Rebecca Lemov, Thomas Sturm, and Michael D. Gordin, How Reason Almost Lost Its Mind: The Strange Career of Cold War Rationality (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013). ↩

-

Konrad Lorenz, On Aggression, translated by Marjorie Kerr (New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, 1966). On Lorenz’s variable use of animal metaphors in his writings, see Tania Munz, “‘My Goose Child Martina’: The Multiple Uses of Geese in the Writings of Konrad Lorenz,” Historical Studies in the Natural Sciences 41/4 (2011): 405-446. ↩

-

Marlene Zuk, Paleofantasy: What Evolution Really Tells Us About Sex, Diet, and How We Live (NY: Norton, 2013). ↩

-

George Gaylord Simpson, Meaning of Evolution: A Study of the History of Life and of Its Significance for Man (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1949), 337. ↩

-

Theodosius Dobzhansky, The Biological Basis of Human Freedom (New York: Columbia University Press, 1956), 107. ↩

-

Leon Stover and Harry Harrison, ed. Apeman, Spaceman (New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1968). ↩

-

Osgood, An Alternative to War and Surrender, 19. ↩