South Asianists never speak of the undead. Africanists do. Latin Americanists do. But not South Asianists. Favoured by a more fulsome textual archive, South Asian historians dwell upon seemingly weightier matters. Historians of science in South Asia are even less interested in the phantomatic.1 Public Health, Foucaultian entanglements of pouvoir/savoir, the global ‘circulation’ of intelligence and even more Public Health usually engage their attention and keep them away from what Jean and John Comaroff have called the “phantom history” of the undead.2 Yet when one allows one’s self the liberty of such distractions, one cannot fail to observe the swarming undead of the Raj.

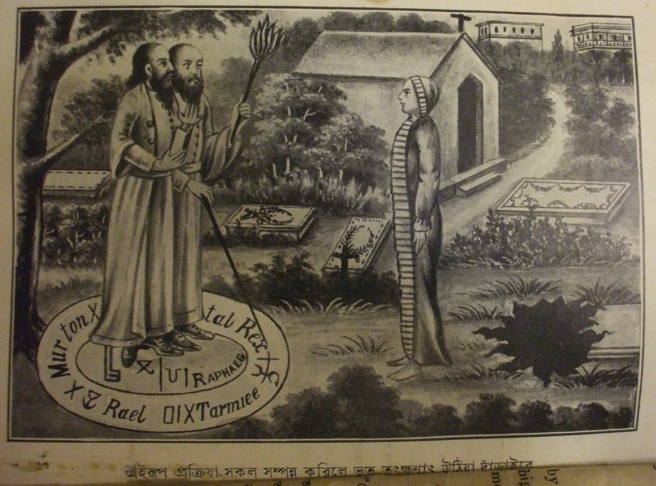

An illustration accompanying an undated but published Bengali collection of spells for raising the dead. The illustration is copied from a woodcut published by the English Swedenborgian, Ebenezer Sibly, in 1784. The illustration originally depicted the sixteenth century alchemists, Edward Kelley and John Dee, raising the dead. The Bengali collection makes no reference to any of the English figures, but reproduces their spells and incantations in English. The collection possibly dates from the first decade of the twentieth century.

Nowhere were these undead more legion than in British Bengal that formed the cornerstone of the empire. The Bengali undead however, were not the ‘zombies’ of the plantation economies of the Caribbean. There were in fact myriad forms of Bengali undeadness. The Betal (pronounced: Betaal) for instance, was a corpse that had literally been ‘taken over’ by a soul or spirit. The Pishach on the other hand was a ghoul who feasted on corpses.3 Then there is the grave-robbing Ghul from which comes the English term ‘ghoul’, the Afrit or sometimes Akrit, who lurk in ruins and many more. They were all undead, but in different ways. Each of them had their own characteristics and inhabited different niches. What was common to all of them was that they all shared the social space with humans and interacted with them in various ways. They also provided different types of links with the past. Much of this would be familiar to folklorists, students of religion and cultural historians. But what is seldom noted and yet quite remarkable is just how central the undead were to the key projects of 19th century Bengali modernity. The very first textbook of Bengali prose, written by Iswarchandra Vidyasagar—educator, social reformer, erudite scholar and one of the founding fathers of modern South Asia—featured a cycle of tales narrated by a paranimate. The textbook, Betal Panchabinshati [Twenty Five Tales of the Betal] (1847), was written as a primer for the linguistic instruction of young British officers upon arrival. Key legal texts such as Shyamacharan Sarkar’s Vyavyasthya Darpan: A Digest of Hindu Law as Current in Bengal (1859) also invoked pishacha lore in discussing the law of marriages, inheritance and adoption.

What do these undead beings want and why are they so plentiful in 19th century Bengal? A lengthy poem by an unknown Bengali poet, Nabinchandra Das (there is a better-known poet of the same name slightly later, but this is not him), written in an idiom that tries too hard to be polished and published from a cheap Calcutta press, gives a fascinating answer.4 In a lengthy conversation between a Pishacha and a Betal, we find that these undead beings are the bearers of a past that has been erased from human memory. Tellingly, the conversation takes place on the fringes of the blood-soaked battlefield of Plassey. It would be too distracting for us to go into the fascinating details, judgements and histories that were shared by the Pishach and the Betal on that fateful day, but that such a conversation took place testifies to the place and function of the undead in 19th century Bengal. They were not simply ghosts, like Hamlet’s father, looking for someone else to settle their unsettled scores for them. No. These were pasts that lived on. That refused to die. But were yet, neither fully alive nor fully embraced by human society. Even as colonial modernity worked out the precise line dividing zoe from bios at Plassey, on its margins—beyond both zoe and bios—there sat the undead: thinking, talking, judging and living a parallel form of life. This is paranimacy, i.e. para-animacy. Forms of life that run parallel to those circumscribed by the necropolitics of empire.

Paranimates, it is worth noting, are nothing like the ‘living tradition’ that the Hindu or Muslim right-wing speak of. For them, ironically like the rationalist scholarship in history of science, these paranimates can only at best be metaphors not real beings. They can thus be reformatted without any reference to their autonomous being and fitted into neo-traditionalist agendas. They become, like the stuffed beasts of the taxonomist, mere ciphers in a museum devoted to the image of an ossified and purified ‘tradition’. The conversation on the fringes of Plassey on the other hand happened between two paranimate beings. The Pishacha of Plassey denounced the rampant casteism of 19th century Bengali society at length. He linked the defeat at Plassey to the sins committed through numerous everyday acts of gendered violence and most emblematically the horrible custom of widow-burning (Sati). Finally, he recounted a mongrel history of travel and inter-marriages which rendered all nations—Asian and European—kinsfolk. The Pishacha of Plassey would surely offend the Hindu right-wing. But so what? He wasn’t their servant, least of all some stuffed up exhibit in their Hall of Hindu Horrors. He was a paranimate with his own views and life-story, however unpalatable or mongrelized.

In this colonial world, crowded as it was by paranimacies, it was but natural that early Bengali science fiction would also feature paranimates. While the Bengali SF tradition dates allegedly from 1857 when Jagadananda Roy is said to have penned a time travel tale, scholarship on it is remarkably thin. What little exists, copies off each other. Indeed the whole issue of Roy’s priority over Wells, based as it is on an utter lack of any original research in most cases, has produced ludicrous results. James Dator for instance, is one of the more erudite proponents of the 1857 date.5 Yet, for all his scholarly credentials, he does not allow facts to stand in the way of a grand claim. Roy, after all, was born in 1869! The canon that has thus been created by the lazy, internet-enabled, copy-paste-enter mode of inter-textuality makes no mention either of paranamacies or paranimates.

Resurrecting these colonial paranimates, I will argue, allows us to grapple with modes of radical alterity that have been elided not only in the history of SF, but in the history of science more generally. Paranimates subvert the all too familiar human/nonhuman binary for instance, but not in the now fashionable way by keeping ‘western’ ontologies of animacy and humanness intact and invoking either hybrids or nonhumans. Paranimates, by their very existence draw attention to other cosmologies and ontologies, where animacy is neither an exclusively human virtue, nor indeed are humans and nonhumans the only two kinds of beings. Learning from Latin American scholars like Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, I want to re-think animist ontologies in a way that will challenge the continued ontic hegemony of the west. I strongly feel that even seemingly progressive moves such as including the nonhuman in histories of science all too frequently work insidiously to universalize a western-centric ontology of human/ nonhuman, matter/ nonmatter etc. and marginalize any engagement with radically Othered cosmologies.

Such radically Othered cosmologies also engender, I will argue, radically othered ‘sciences’ and ‘practices’ and indeed there have been some very timely calls to expand the very definitions of terms like ‘science’ and ‘practice’ to make history of science more inclusive. But I want to suggest that such inclusiveness, despite its promise of equality, needs to be carefully thought out. What is the cost of incorporation into such universalized terms? Does it not compromise the very possibility of radical alterity? Does it not undermine our most radical hopes that in marginalized, radically Othered cosmologies there are intimations of a more equitable political ecology? By seeking admissions into a broader church of ‘science’ will we not compromise our untranslatable heterodoxy? After all, did Jean Baudrillard not show us that the only radical alterity is that which cannot be translated into a version of the familiar?

It is this radical alterity that I hope, perhaps impossibly and precociously, to resurrect. In the subsequent blogposts therefore, I will reanimate the paranimate ontologies that lie buried in the Bengali SF archive of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Such reanimation and the forgotten cosmologies they will evoke, I’ll suggest might illuminate not only radically Othered images of science, but also locate in these radically Othered images forgotten temporalities that eschew the forward-moving linear teleologies of progress and science. For as Walter Benjamin reminds us, “the true picture of the past flits by. The past can be seized only as an image which flashes up at the instant when it can be recognized and is never seen again.”

-

Banu Subramaniam’s new book Ghost Stories for Darwin is a brave attempt to change this, but her ghosts, at the end of the day, are purely metaphorical. The undead as a metaphysical and socio-historical reality are still clearly unacceptable to historians of science. Ghost Stories for Darwin: The Science of Variation and the Politics of Diversity (Champagne: University of Illinois Press, 2014). ↩

-

Jean Comaroff & John Comaroff, “Alien Nation: Zombies, Immigrants and Millenial Capitalism,” South Atlantic Quarterly 101/4 (2002), 783. ↩

-

For a great discussion on Vetalas and Pisacas (as they are called in classical Sanskrit) see, Justin McDaniel. ↩

-

Nabinchandra Das, Pishachoddhar (Calcutta: Iswarchandra Basu, 1863). ↩

-

James A Dator, Social Foundations of Human Space Exploration (New York: Springer, 2012), 9. An identical claim by Sukanya Datta in the journal Science & Culture is available here. ↩