In June of 2015 Jurassic World, the fourth installment of the movie franchise begun in 1993 with Jurassic Park (the novel was published in 1990), broke the record for biggest opening weekend in box office history.

During the weeks leading up to the official opening, an exquisitely sophisticated marketing apparatus pumped hype through the arteries of major cities around the world. I witnessed this first hand. In Tel Aviv, the film was advertised on a billboard as large as Indomitus rex—the monstrous hybrid that wrecks havoc on the rebuilt Jurassic World theme park. In train stations in Berlin and Paris, announcements that the dinosaurs had arrived were posted along side updates of train times announcing, “The Park is Now Open.”

Jurassic World advertisement at the Hermannplatz subway station in Berlin

With Jurassic World—and its marketing campaign—we learn that the ability to stand beside our no-longer extinct brethren may be the most banal element of what technoscience is up to. People have become jaded—a hyper-realistic website prominently indicates where visitors can get churros in between feedings—which justifies the attempt to engineer spectacularly horrifying creatures. Indomitus rex is meant to be to Tyrannosaurus rex as Godzilla is to a pet iguana. (However, spoiler alert: In the final scenes of the movie T. Rex ultimately triumphs with help from “Blue,” a well-trained Velociraptor).

Months earlier, a slick three-minute promotional clip attributed to InGen, the fictional corporation behind the disasters that took place on the Costa Rican island, Isla Nublar in Jurassic Park, made the rounds on social media. I worked in media relations before returning to academia and such a clip would be part of any savvy public relations rehabilitation strategy. In it, a new generation of employees donned crisp white lab coats as they spoke directly to the camera and explained how today’s science had resolved and redefined the problems of the past. InGen sought to rebrand itself as placing the world at humanity’s fingertips, “deepening our connection to the natural world,” and allowing us to design life for purposes that include health, communication, and defense. As one of InGen’s new generation of hotshots put it, “There’s literally no limit to what we can learn from these creatures.”

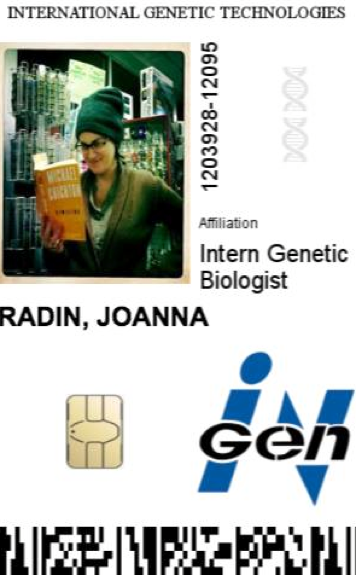

In 2015, InGen’s corporate slogan declared, “Tomorrow. Today.” It was persuasive. I was tempted to believe in the reality of InGen and its vision. I could even take up virtual (if unpaid) employment.

InGen ID card

The viral campaign did not stop there. Not only were the potential unintended consequences of the virtual laboratory addressed and summarily dismissed, a website appeared for the multi-national corporation responsible for its financial revivification. Multiple short films appeared on www.masraniglobal.com, produced to persuade shareholders that their investment decisions were sound. The cool blue tones of the website betrayed very little, if any, connection to the Jurassic World theme park or movie, instead drawing on now generic conventions of corporate branding, including an emphasis on “vision, innovation, and success.” A “live” stock ticker—charting the real time flows of capital—completed the illusion. (After the film premiered, an “urgent memo” from headquarters appeared on this page, indicating that “due to unforeseen circumstances at Jurassic World, resulting in the worst financial crisis the company has ever seen, Masrani Global Corporation will be holding an emergency meeting to discuss the future of the company and its various subsidiaries.”)

In these ways, the marketing of Jurassic World was as much a part of the spectacle, of the experience, as the movie that ostensibly justified its creation. This kind of assemblage is known as “media mix,” which, in recent years, has become a key strategy deployed by movie studios for deepening the immersive experience.1 (It’s also a strategy for making sense of the multimedia enterprise that accompanied Bruno Latour’s An Inquiry into the Modes of Existence, a project that asked, “how do we compose a common world?”)

Together, the movie and the advertising apparatus advance the conceit that our planet has become a giant theme park, Jurassic World. Does it matter whether or not the laboratories and corporations are real? Whether we can actually visit the theme park or merely know the ways in which it is possible to exist? Can this kind of simulacra—the immersive experience that is meant to stand in for but not be reality—create a space in which nonscientists are invited to speculate what else can be produced by science? The virtual representation life augmented by science, its fictive reality, thus becomes a source of its critique.

This kind of place—the space of immersive, authentic recreation as well as its commodification—was a central preoccupation of Michael Crichton, author of the best-selling series of novels on which the movie franchise is based. Long before he wrote about dinosaurs, he explored theme of the amusement park in his 1973 film Westworld (it was never published as a book). It features a vacation destination comprised of three historically specific worlds, the American Wild West (cowboys), the Middle Ages (knights), and ancient Rome (gladiators). Upper middle class people could visit as they would any all-inclusive resort. Each world was populated by androids capable of having sex and being killed—this seems to be the full range of their human skill set—for the sake of placating the visitor’s id. The conceit remains potent enough to justify a remake currently underway at HBO.

A theme park was also at the core of Crichton’s 1999 novel, Timeline, which required travel to 14^th^ century Europe. In this novel, which was subsequently made into a movie and a video game, a brilliant but amoral physicist-cum-entrepreneur builds a time machine. With it people can visit the past as they would an amusement park. Of course, things go horribly wrong. But before they do the cynical impresario reveals his prescience:

“Authenticity will be the buzzword of the twenty-first century. And what is authentic? Anything that is not devised and structured to make a profit. Anything that is not controlled by corporations. Anything that exists for its own sake, that assumes its own shape. But of course, nothing in the modern world is allowed to assume its own shape. The modern world is the corporate equivalent of a formal garden, where everything is planted and arranged for effect. Where nothing is untouched, where nothing is authentic. Where then will people turn for the rare and desirable experience of authenticity? They will turn to the past . . . .The past is real. It’s authentic. And this will make the past unbelievably attractive. That’s why I say that the future is the past.” (Italics his, p. 401)

Timeline relied upon a mix of science and business to bring the present to the past, in ways that resonate with how Jurassic Park brought the past to the present, and Jurassic World promises to bring the future to the present, with InGen’s slogan, “Tomorrow, Today.”

When Jurassic Park was made into a movie in 1993—before Craig Venter founded Celera to overtake the federally funded Human Genome Project—Crichton’s coupling of science and capitalism was interpreted as an indictment of science more generally. The New York Times ran a long opinion piece titled, “Evil Science Runs Amok—Again,” in which the author, a Professor of English at the University of Southern California, criticized the portrayal of science and scientists.2 Carol Dukes wrote, “To the creators of ‘Jurassic Park,’ technological advance is virtually a no-win . . . With this attitude on the part of the purveyors of popular culture, how can we expect to attract young students to science, a field they are snubbing in droves?”

What Dukes could not have known in advance was that her text would be wrapped around an advertisement for Mobil, formatted like a short article. “Cradle science” featured a cartoon of an infant in her crib engrossed by a computer screen (“by the year 2000,” the ad emphasizes, “60 percept of our workforce will be women, immigrants and people of color”). “At Mobil,” the reader was informed, “we’re helping students learn to analyze by providing learning materials to promote better critical thinking at 24,000 high schools nationwide.” This juxtaposition was ironic on multiple levels, not least of all the fact that oil—Mobil’s source of wealth—is mined and processed from organic material that has been stewing in the earth’s crust since the Jurassic period.

Science Gone Amok/Cradle Science

In 1999 Crichton was asked to speak to the members of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) about the purported tension between science and the media. This forum provided him with an opportunity to address his detractors. It can be read as a response to critiques of his depiction of science as well as a commentary on the media context by which such critiques reach readers.

“We live in a culture of relentless, round-the-clock boosterism for science and technology. With each new discovery and invention, the virtues are always oversold, the drawbacks understated. Who can forget the freely mobile society of the automobile, the friendly atom, the paperless office, the impending crisis of too much leisure time, or the era of universal education ushered in by television. We now hear the same utopian claims about the Internet. But everyone knows science and technology are inevitably a mixed blessing. How then will the fears, the concerns, the downside of technology be expressed? Because it has to appear somewhere. So it appears in movies, in stories—which I would argue is a good place for it to appear.”3

In this light, Crichton’s depiction of science takes on a different inflection. Rather than a luddite-like critic, he begins to resemble an agent shaping the ways in which science can be subjected to critique and potentially redeemed.

A century earlier, Arthur Conan Doyle or Edgar Allen Poe—two experts in mixing literary cocktails of wonder and reason—created realist immersive worlds that revealed glimmers of enchantment in the supposedly disenchanted world inhabited by their readers. As Michael Saler has argued of these writers, “fantasy helps us accept that the real world is to some degree imaginary, relying on contingent narratives that are subject to challenge and change.”4 Crichton’s theme parks do the same—they present us with the problems and possibilities that animate our obsession with authenticity.

Michael Crichton receives a creative credit in Jurassic World, but he played little if any role in the writing or production of the film, given that he died in 2008. However, the spirit of his fiction—which serves as a means for posing new kinds of questions about science, technology, and capitalism—is most alive in the marketing campaign. It’s there that the fictive reality and values of the scientific life are rendered most sharply: a world in which scientists become spokespeople and businessmen become benefactors and we take pleasure, comfort, and health from the byproducts. Our world is Jurassic World, and its boundaries stretch far beyond the cinema.

-

Frank Rose, The Art of Immersion (New York: W.W. Norton, 2011). ↩

-

Carol Muske Dukes, “Evil Science Runs Amok—Again!” The New York Times, June 10, 1993. ↩

-

Michael Crichton, “Ritual Abuse, Hot Air, and Missed Opportunities: Science Views Media,” American Association for the Advancement of Science, January 25, 1999. ↩

-

Michael Saler, As If: Modern Enchantment and the Literary Prehistory of Virtual Reality (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012), 21. ↩